According to the Wiki: On this day in 1947 The Screen Actors Guild implements an anti-Communist loyalty oath.

With the election of racist, xenophobic, and mysoginyst Donald J. Trump, it’s more important than ever to use this as a learning experience, unless we want to repeat it.

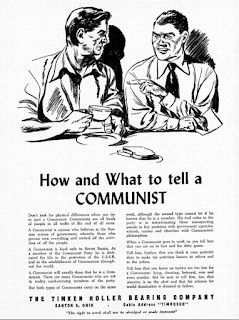

The Loyalty Oath came during the Communist Witch Hunts of the ’40s and ’50s, in which both Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan made their bones. It was the era of Joseph McCarthy. ‘Merkins were being warned that there were Communists under every bed, or inside every pumpkin in the case of Nixon.

The House Un-American Activities Committee ramped up in 1938 to find subversives and Communists in ‘Merka, not that it was illegal to be a Commie. By the next year HUAC issued its “Yellow Report,” which called for the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

When the war ended HUAC considered briefly investigating the KKK, but decided against it to go after Commies some more. That led to 9 days of hearings in 1947 on Communist influence in the entertainment industry, most notably Hollywood. Ronald Reagan, who was President of the Screen Actors’ Guild, went before HUAC and, famously, named names.

The Wiki has more:

Many of the film industry professionals in whom HUAC had expressed interest—primarily screenwriters, but also actors, directors, producers, and others—were either known or alleged to have been members of the American Communist Party. Of the 43 people put on the witness list, 19 declared that they would not give evidence. Eleven of these nineteen were called before the committee. Members of the Committee for the First Amendment flew to Washington ahead of this climactic phase of the hearing, which commenced on Monday, October 27.[22] Of the eleven “unfriendly witnesses”, one, émigré playwright Bertolt Brecht, ultimately chose to answer the committee’s questions.[23][24]

The other ten refused, citing their First Amendment rights to freedom of speech and assembly. The crucial question they refused to answer is now generally rendered as “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?” Each had at one time or another been a member, as many intellectuals during the Great Depression felt that the Party offered an alternative to capitalism. Some still were members, others had been active in the past and only briefly. The Committee formally accused these ten of contempt of Congress and began criminal proceedings against them in the full House of Representatives.

In light of the “Hollywood Ten”‘s defiance of HUAC—in addition to refusing to testify, many had tried to read statements decrying the committee’s investigation as unconstitutional—political pressure mounted on the film industry to demonstrate its “anti-subversive” bona fides. Late in the hearings, Eric Johnston, president of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), declared to the committee that he would never “employ any proven or admitted Communist because they are just a disruptive force and I don’t want them around.”[23] On November 17, the Screen Actors Guild voted to make its officers swear a pledge asserting each was not a Communist.

The Screen Actors Guild Loyalty Oath implemented on this date in 1947 continued for decades. Actor and former-SAG President Richard Masur is quoted in 50 YEARS: SAG REMEMBERS THE BLACKLIST as saying:

“When I joined the Screen Actors Guild in 1973, I signed the loyalty oath that, 20 years earlier, the SAG Board of Directors had made a requirement for membership. I never stopped to consider what it was I was signing. It was one in a series of papers I needed to fill out, and I was so eager to join the Guild, I probably would have signed anything they put in front of me. And I did. That’s one of the most frightening legacies of the Blacklist Era: the institutionalization of fear and prejudice.

You see, the Guild Board had not yet removed the loyalty oath from our bylaws. In fact, no action was taken until some new members refused to sign it. Those new members were the rock group The Grateful Dead, and the year was 1967.

Only after The Grateful Dead refused to sign did the Board of Directors reconsider the necessity of a loyalty oath as a precondition for joining a union of artists. Even so, the oath had become so ingrained and institutionalized by that time that initially it could not be entirely eliminated. It was simply made optional. Another seven years would pass before, in July of 1974, a year after I joined, the loyalty oath was finally removed from the Screen Actors Guild bylaws.

That’s right. It was the Grateful Dead that finally broke the back of the Loyalty Oath. Masur continues, as he make amends on the 50th Anniversary of the Oath:

Tonight, the Screen Actors Guild would like to express how deeply we regret that when courage and conviction were needed to oppose the Blacklist, the poison of fear so paralyzed our organization.

Only our sister union, Actors Equity Association, had the courage to stand behind its members and help them continue their creative live [sic] in the theater. For that, we honor Actors Equity tonight.

Unfortunately, there are no credits to restore, nor any other belated recognition that we can offer our members who were blacklisted. They could not work under assumed names or employ surrogates to front for them. An actor’s work and his or her identity are inseparable.

Screen Actors Guild’s participation in tonight’s event must stand as our testament to all those who suffered that, in the future, we will strongly support our members and work with them to assure their rights as defined and guaranteed by the Bill of Rights.

With the ugly hate rhetoric that came out of the Trump campaign, we could do worse than remembering how the Grateful Dead stood up for the First Amendment. And, with Donald Trump about to take the oath of office for POTUS, it’s incumbent on all of us to stand up for Muslims, Immigrants, Mexicans, LGBT communities, and Black folk and not allow the hate to define us.

The same goes for Trump supporters.

they refused to sign the Screen Actors Guild Loyalty Oath.